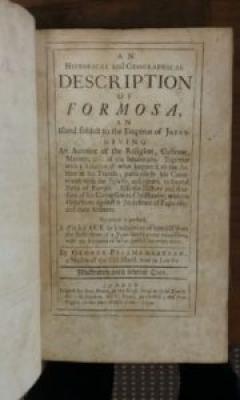

The island of Taiwan, once commonly known in the West by the Portuguese name of Formosa, has recently resurfaced in the news in connection with the One China policy. In the past it was also a subject of interest, although information coming from Taiwan itself was often scarce. Because of that scarcity it was possible in 1704 for a European to appear in London claiming to be a Formosan and to publish a book about the island that was fiction masquerading as a true travel account. Special Collections has just acquired a first edition of one such work with funds from the Gale H. Arnold '58 Special Collections Endowment.

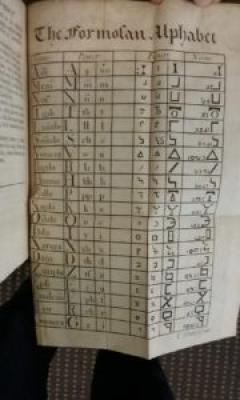

The author of the work called himself George Psalmanaazaar. He was a Frenchman educated by the Jesuits. Although he wrote an autobiography that was published posthumously, he never gave away his real name and it remains unknown to this day. He used the accounts of Jesuits who had been active in China and Japan, as well as conventions from other travel accounts about exotic places to write his own story and to inform his own performance. In fact, the whole episode was one long charade, with Psalmanaazaar adopting unusual habits like eating raw meat and sleeping upright, which he thought would contribute to people believing that he really was from a different culture. He even invented an alphabet and language for the place he claimed to be from, and the book contains a fold-out sheet of the former and 'translations' into his language:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the truth of Psalmanaazaar's story was challenged before the Royal Society, the premier scientific organization in Britain. His particular opponent was a Jesuit priest who had spent many years in missions in Asia, though not in Formosa; the priest knew the area and, with the benefit of expertise, attacked Psalmanaazaar's assertions. However, the fact that he was a Catholic priest, and that Psalmanaazaar framed his whole narrative as an attack on the Jesuits – never popular in Protestant England – meant that he was able to hold his position with the support of anti-Catholics. Thus Psalmanaazaar reminds us that claims to knowledge about something often involve two threads: the assertion of truth and attacks on opponents who disagree. When compared with the second "corrected" edition, which addressed some of the claims that the author was not who he said he was—a copy of which was already in our rare books holdings—this book is an excellent way to explore how people three hundred years ago had to negotiate issues of truth or fiction in ways that seem to have resurfaced along with our recent discussions of Taiwan.